, Edited by Explained Desk | New Delhi |

Updated: November 16, 2020 11:52:18 am

The entrance of an eatery is locked after it closed down due to pandemic in Bengaluru (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Dear Readers,

The festive season around Diwali is typically a time when Indians look back at the year gone by as well as look forward to the year ahead. In this regard, the Indian economy is going through one of those curious phases when it is possible to argue diametrically opposite things about it.

Let’s start with something that affects us all everyday — price rise or the inflation rate.

Retail inflation — calculated by using the Consumer Price Index — surged to a 77-month high of 7.61 per cent in October. In other words, the rate at which retail prices increased in October is the highest since May 2014 — the month when Narendra Modi first took charge as India’s Prime Minister.

High inflation, especially double-digit food inflation as is the case today, was one of the main reasons why people were unhappy with the United Progressive Alliance government towards the end of 2013. Further, controlling the general level of prices has been one of the key successes of the Modi-led government in New Delhi.

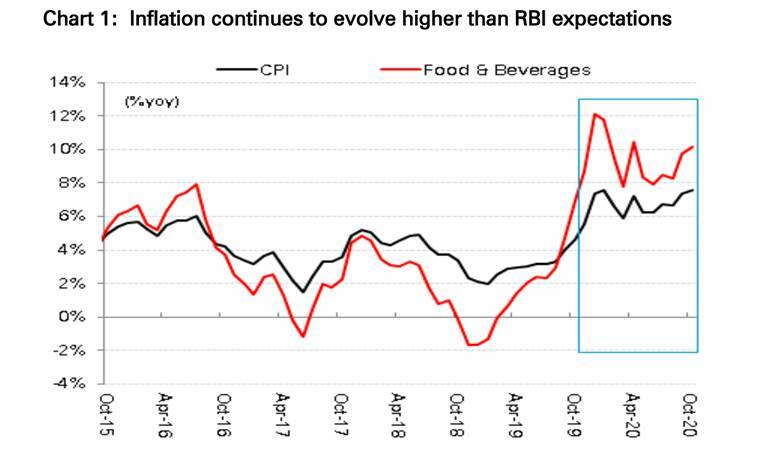

But over the past 11 months, as shown in the chart below (Source: ICICI Securities), the retail inflation rate has been above the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) comfort zone. For the record, RBI targets a retail inflation rate of 4% and can allow it to vary between 2% and 6%.

Inflation continues to evolve higher than RBI expectations (Source: ICICI Securities)

Inflation continues to evolve higher than RBI expectations (Source: ICICI Securities)

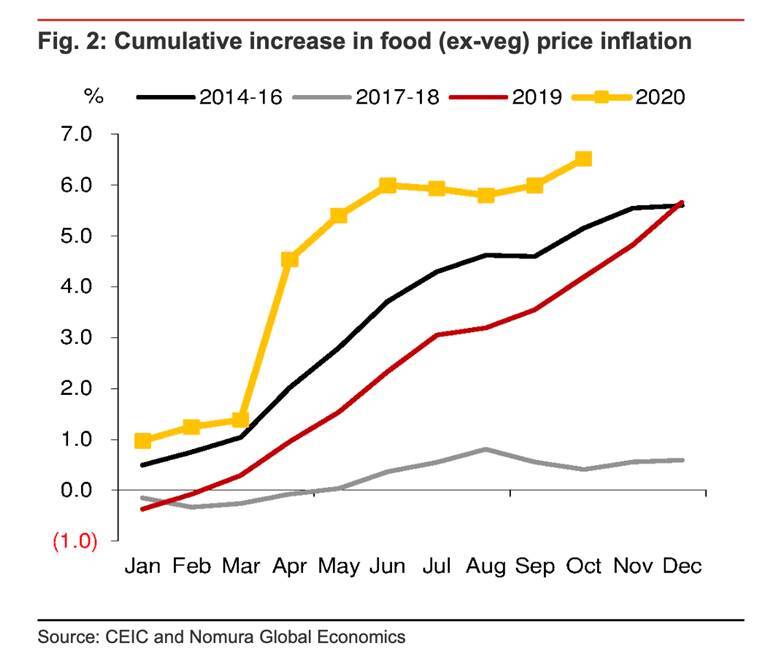

Since November 2019 — that is, well before Covid-19 hit the world or Indian economy — retail inflation has trended consistently higher than expected. Much like the same time last year, unseasonal (and excessive) rains are the main reason for the spike in food prices. Higher fuel costs, thanks to high taxation by the government, have not helped. And Covid-induced supply disruptions have only made things worse. The chart below (Source: Nomura) shows how the cumulative increase in food price inflation in 2020 has been the highest-ever since 2014.

Don’t miss from Explained | What is a technical recession?

The cumulative increase in food price inflation (Source: Nomura)

The cumulative increase in food price inflation (Source: Nomura)

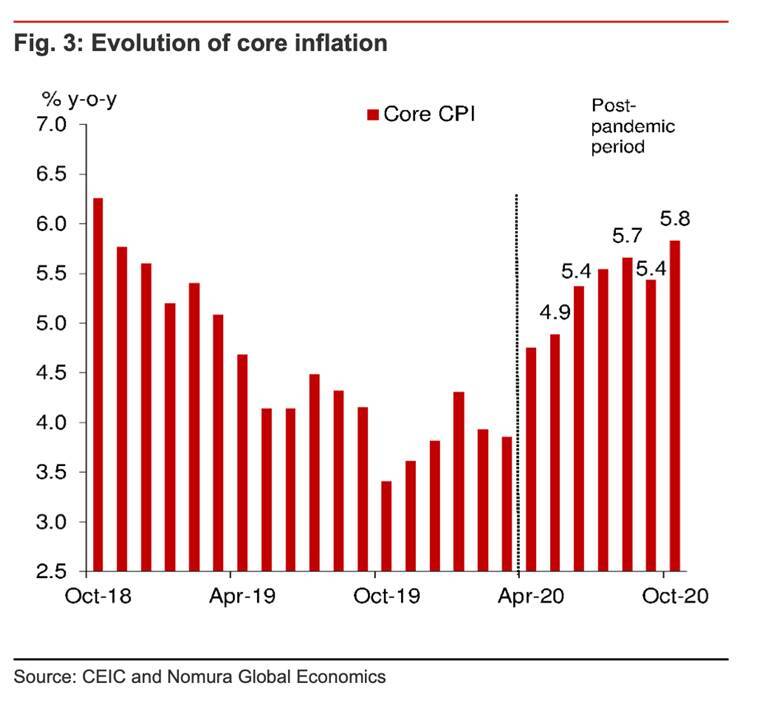

Further, even “core” inflation (that is, inflation rate without taking into account the prices of food and fuel, which tend to fluctuate the most) has steadily hardened since November 2019 (see chart below; Source Nomura). The persistence of high core inflation is perhaps the most worrying trend.

The most immediate implication of such high inflation in October is that RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee, which is scheduled to sit on December 5 to deliberate whether to cut interest rates (to encourage economic activity), will most likely dither from doing so.

Looking back over the past 12 months, one finds that RBI has missed its inflation target for one reason or another. And that trend seems to be continuing. According to a research note by ICICI Securities headline inflation for the current quarter — that is, October to December — “looks set to evolve almost 1% higher compared to RBI estimate of 5.4% average for the same period”.

Don’t miss from Explained | Tax relief until June next year: should you buy a new home now?

Evolution of core inflation (Source: Nomura)

Evolution of core inflation (Source: Nomura)

What is peculiar still about the current inflationary trend is that its future is highly debatable. Economists are divided whether the inflation will come down henceforth or continue to stay elevated. For instance, while ICICI Securities states that “we continue to expect that food inflation should recede in coming months,” CARE Ratings states “inflation will remain elevated for the next few months”.

If we look at GDP growth, again, it is anyone’s guess right now what will happen. On the face of it, as the RBI stated in its November’s monthly bulletin, India entered a “technical” recession in September. A country is said to have entered a technical recession if its GDP growth rate stays in the negative territory for two consecutive quarters.

And yet, according to the RBI as well as Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, September-end will likely mark a turnaround for the economy. The RBI stated: “Incoming data for the month of October 2020 have brightened prospects and stirred up consumer and business confidence… If this upturn is sustained in the ensuing two months, there is a strong likelihood that the Indian economy will break out of contraction of the six months gone by and return to positive growth in Q3:2020-21, ahead by a quarter of the forecast provided in the resolution of the monetary policy committee on October 9, 2020”.

But, it is can also be argued that Indians are savings more and more — household financial savings jumped to 21.4% of GDP in the first quarter of 2020-21, up from 10% in the fourth quarter of 2019-20 — and, in the absence of incomes rising fast enough, this behaviour will likely inhabit fast economic recovery. 📣 Express Explained is now on Telegram

Let’s take another keenly watched variable — employment.

As many of you know, India’s annual GDP growth fell sharply between 2017-18 (7%) and 2019-20 (4.2%). A CARE Ratings study of over 1700 companies to evaluate the incremental employment, found that this deceleration had a sharp impact on the number of incremental (or new) employment. Barring Banks and FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods such as packaged food and toiletries), all other sectors employed fewer new people in FY20 as against FY19 (see table below).

Incremental employment of above 1000 in sectors (Source: CARE calculation)

Incremental employment of above 1000 in sectors (Source: CARE calculation)

“As the pandemic induced lockdown has led to significant rationalization in headcount in several sectors, the picture for FY21 would be more negative than in FY20,” notes the study.

Moving one, let’s look at the state non-performing assets (NPAs) in the banking sector.

On the face of it, gross NPAs of 31 banks have fallen from 8.7% of all advances in December 2019 to 7.7% of all advances in September 2020. But, if one goes behind these numbers, one can spot that this improvement is essentially because of the moratorium provided by the RBI — and not because companies are paying back their dues on time. Most analysts will caution you to watch out for a possible surge in NPAs once such regulatory forbearance is over.

Lastly, on the policy front, too, this notion sustains.

Shoppers and pedestrians walk past stalls at the Bhadra Fort market in Ahmedabad (Photographer: Sumit Dayal/Bloomberg)

Shoppers and pedestrians walk past stalls at the Bhadra Fort market in Ahmedabad (Photographer: Sumit Dayal/Bloomberg)

Last week, the government announced the third tranche of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan package. A key initiative is the Production Linked Initiative worth up to Rs 1.46 lakh crore for 10 key sectors in a bid to boost India’s manufacturing capabilities and enhance exports.

Now, it can be argued that the PLI will help the Indian economy but it can also be argued that this scheme is spread over the next 5 years and it is unlikely to result in any new expenditure by the government in the current year.

Speaking of government expenditure, the actual additional spend by the government unders the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan 3.0 is again much smaller than what initial announcements may suggest.

There is only one thing on which there is no debate: All of us need to wear a mask to stay safe from Covid.

Udit

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd