The electoral matters committee, chaired by upper house Labor MP Lee Tarlamis, will examine “truth in political advertising” laws that would make it a civil offence to publish election material containing false information that purports to be a statement of fact.

Labor MP Lee Tarlamis is heading the inquiry.Credit:Victorian Parliament

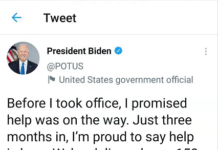

“Social media has changed the way we campaign at elections. It gives people instant access to different viewpoints and makes it easy for people to connect with political candidates. But it can also be used to spread fake news,” Mr Tarlamis said.

“There are genuine concerns in the community about the way new technologies appear to be impacting elections in this state.”

The laws have existed in South Australia since 1985 and the ACT government this year banned false political advertising. Politicians in the territory were motivated by two recent federal election issues – Labor’s “Mediscare” campaign and the Coalition’s “death tax” warning – that were widely accepted to be untrue or, at best, misleading.

Fines of between $5000 and $25,000 apply to those who breach the South Australian law. The SA electoral commissioner, who adjudicates complaints about false ads, requested 17 retractions or withdrawals during the past two state elections.

The laws could apply to social media companies if the platforms could reasonably have been expected to know the political advertisement was misleading or deceptive.

The prospect of similar laws in Victoria has already proved divisive. The state Labor Party, Victoria’s peak union body and the Centre for Public Integrity welcomed truth laws being examined. Radio and TV industry bodies expressed opposition to the laws and say political parties, not broadcasters, should be liable for misleading advertisements.

The Victorian Electoral Commission, in its submission to the inquiry, said the laws would be open to manipulation by political parties and argued the rules would not effectively capture the gamut of ways by which political actors could seek to act deceptively, including through omission of context, use of literary devices or manipulative targeting.

“The VEC does not consider its role to be an arbiter of ‘truth’ … The VEC is not an authority on the myriad of issues that arise in an election, and it would be an overreach for the VEC to purport to determine the truth in such issues,” the commission’s submission states. It adds delays in assessing complaints and potential non-co-operation by platforms could reduce the effectiveness of the laws.

Loading

Luke Beck, an associate professor in constitutional law at Monash University, is urging the committee to recommend laws modelled on the accepted commercial definition of deceptive and misleading advertising. The laws would be policed by Consumer Affairs Victoria, which already monitors deceptive commercial advertising.

“If someone says Bill Shorten will ruin the economy, that’s not deceptive or misleading – it’s just puffery,” he said. “Whereas if someone says Labor has a plan for a death tax, that’s a statement about a fact that is false.”

The inquiry, which will hold virtual public meetings, will also examine government support for fact-checking organisations and whether to require public disclosure of all online political advertising and its funding source.

Start your day informed

Our Morning Edition newsletter is a curated guide to the most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Paul is a reporter for The Age.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading